主页--->m-comment-000--->mb-comment-012-120

|

电脑版 |

|||||||||||||||||

布罗克斯顿评说莫里康内 MB-012-120 |

||||||||||||||||||

Ennio Morricone, 1928-2020 |

||||||||||||||||||

Ennio Morricone, 1928-2020 |

||||||||||||||||||

作者 乔纳森·布罗克斯顿 (Jonathan Broxton) |

||||||||||||||||||

ENNIO MORRICONE 评论,第12部分 012-120 |

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

埃尼奥·莫里康内,1928-2020 年 2020.7.6

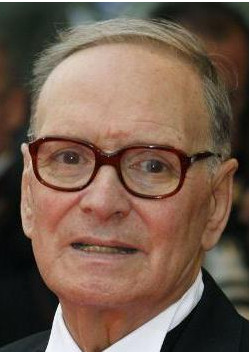

作曲家埃尼奥·莫里康内(Ennio Morricone)于2020年7月6日在意大利罗马的医院去世,此前他在家中摔倒并摔断了腿,出现并发症。享年91岁。 埃尼奥·莫里康内于1928年11月出生于意大利罗马。他曾就读于圣塞西莉亚国立音乐学院,专攻小号演奏和作曲。在50 年代,莫里康内为 RCA 唱片公司改编流行歌曲,其中包括为 Paul Anka、Chet Baker 和 Mina 等艺术家改编的一些歌曲。在RCA工作期间,莫里康内还创作了戏剧音乐和古典作品,最终成立了Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanzsa,这是一个前卫的音乐即兴创作团体,被认为是最早的实验作曲家团体之一。 莫里康内在1950年代后期开始为阿曼多·特罗瓦约利(Armando Trovajoli)和马里奥·纳西姆贝内(Mario Nascimbene)等作曲家代笔,然后在1961年在导演卢西亚诺·萨尔斯(Luciano Salce)的《法西斯主义者》(Il Federale)首次亮相。1960 年代,他几乎只在意大利电影界工作,但因与前同学,导演,塞尔吉奥·莱昂内 (Sergio Leone) 的合作而开始获得一些国际知名度,他的“意大利面条西部片”由一位名叫克林特·伊斯特伍德的年轻美国演员主演,出乎意料地大受欢迎。《荒野大镖客》(1964年)、《黄昏双镖客》(1965年)、《好坏丑》(1966年)和《西部往事》(1968年),以及伯特·雷诺兹(Burt Reynolds)的《纳瓦霍乔》(1966年),向世界介绍了他独特的个人风格,将传统管弦乐队与不寻常的打击乐效果、粗鲁的吟唱声、 亚历山德罗·亚历山德罗尼(Alessandro Alessandroni)不寻常的口哨声,以及他的朋友、女高音歌唱家埃达·德尔·奥尔索(Edda dell'Orso)的嗓音高亢优美。这些配乐产生了巨大的影响力和广受欢迎的音乐,迅速巩固了他作为欧洲领先电影作曲家之一的声誉。 1960 年代末和 1970 年代初,莫里康内拓宽了他的视野,在欧洲各地为各种可以想象的类型的电影配乐,并首次涉足好莱坞。他经常合作的导演包括达里奥·阿金托、马可·贝洛基奥、贝尔纳多·贝托鲁奇、毛罗·博洛尼尼、泰伦斯·马利克、朱利亚诺·蒙塔尔多、阿尔贝托·内格林、皮尔保罗·帕索里尼和吉洛·庞泰科尔沃等导演,他为《萨拉修女的两头骡子》(1970)、《革命往事》(1971)、《无名小子》(1973)、《萨罗》(1975)、《1900新世纪》(1976)和《天堂的日子》(1978 年)谱曲,他因此获得了他的第一个奥斯卡金像奖提名。 1980 年代和 1990 年代,莫里康内更频繁地被美国导演雇用,他在此期间最受欢迎的一些配乐获得票房成功,例如约翰·卡彭特的《突变第三型》(1982 年)、布莱恩·德·帕尔马的《义胆雄心》(1987 年)、《一代情枭-毕斯》(1991 年)、《火线大行动》(1993 年)、Barry Levinson 的《狼人恋》(1994 年)和《叛逆性骚扰》(1994 年), 以及重要的杰作,如《美国往事》(1984 年)、罗兰·乔菲的《教会》(1986 年)、《越战创伤》(1990 年)和朱塞佩·托纳托雷的三部曲《天堂电影院》(1991 年)、《新天堂星探》(1997 年)和《海上钢琴师》(1999 年)。 在1998年《美梦成真 》的配乐被拒绝后(在那里他被迈克尔·卡门取代),在2000年布莱恩·德·帕尔马(Brian De Palma)的《火星任务》中经历了相当痛苦的后期制作时期,莫里康内退出了好莱坞的作曲界,而是宁愿留在欧洲,主要为意大利电影和电视项目写作。 在那里,他仍然多产,在千禧年之交后为超过 75 部电影配乐。2015年,他为导演昆汀·塔伦蒂诺(Quentin Tarantino)执导的最后一部美国电影《八恶人》为他赢得了姗姗来迟的奥斯卡最佳原创配乐奖; 莫里康内曾获得五项奥斯卡金像奖提名——2000 年的《天堂的日子》、《教会》、《义胆雄心》、《一代情枭-毕斯》和《玛莲娜》——但没有获奖,然后在 2007 年被授予奥斯卡荣誉奖,“以表彰他对电影音乐艺术的宏伟和多方面贡献”,成为继亚历克斯·诺斯之后第二位获此殊荣的作曲家。除此之外,莫里康内还在他的家乡意大利获得了三项金球奖(来自 9 项提名)、六项英国电影学院奖、四项格莱美奖和十项大卫·迪·多纳泰罗奖。 《好、坏,丑》的主标题,以及该乐谱的压轴作品《黄金的狂喜》,成为莫里康内的两首标志性作品。莫里康内在电影《玛达莲娜》(1971年)和《职业杀手》(1981年)以及电视连续剧《英国人的城堡》(1978年)和《大卫·劳埃德·乔治的生平与时代》(1981年)中出现的非电影作品“Chi Mai”也非常受欢迎,并且由于它出现在英国电视上,该主题在2年的英国单曲排行榜上排名第二。 除了电影作品外,莫里康内还创作了许多古典作品,并在世界各地指挥了许多乐团,包括伦敦爱乐乐团、纽约爱乐乐团和伦敦交响乐团。自1990年代中期以来,他一直是罗马小交响乐团的主要指挥之一,自2001年以来在世界各地指挥了200多场音乐会。他与妻子玛丽亚·特拉维亚(Maria Travia)住在罗马,并于1956年结婚。他们有三个儿子和女儿:马可、亚历山德拉、安德里亚——他也是一位作曲家和指挥家——以及居住在纽约市的电影制片人乔瓦尼。 ========================= 在这一点上,我想对莫里康内做一些个人表达。我有幸在伦敦两次看到他的音乐,2001年在巴比肯,然后是2003年在皇家阿尔伯特音乐厅,这两次活动都是对他和他的音乐的壮观庆祝。我只见过他一次面,那是在2016年2月,当时他前往洛杉矶参加奥斯卡颁奖典礼。作曲家和作词家协会为当年的音乐提名者安排了招待会,我能够与他握手并摆姿势与他合影留念。由于他拒绝学习英语,并且考虑到我的意大利语几乎为零,我只对他说了两个字——“mille grazie”(笔者注:意大利语“非常感谢”)——不仅感谢他的合影,而且感谢他一生中为音乐所做的一切。他回答说了一句“prego”(笔者注:意大利语“请”),并给了我一个小小的微笑,仅此而已。 但我亲眼目睹的一件神奇的事情是莫里康内和约翰·威廉姆斯之间的对话,约翰·威廉姆斯也在那一年被提名。这两位音乐巨人坐在一起,全神贯注地交谈了15分钟以上,在埃尼奥的儿子乔瓦尼翻译时,他们生动地聊天。我站在离他们只有几英尺远的地方,我真的分不清在说什么,但令我震惊的是,这是一个标志性的时刻。这就像在看莫扎特和贝多芬、莎士比亚和狄更斯、达芬奇和梵高之间的对话,如果这些人没有被时间和地理分开的话。 莫里康内是多么有影响力,多么才华横溢,多么天才,几乎怎么夸大都不为过。莫里康内没有在钢琴上作曲,也没有使用电脑。他用一支铅笔和一张五线谱纸,写下了他脑海中的想法。令人惊讶的是,有一天早上,他坐下来写了一些音乐,然后到一天结束时,“黄金的狂喜”存在于世界上。或“加布里埃尔的双簧管”。或“黛博拉的主题”。或者他在职业生涯中写下的数十个标志性主题中的任何一个。而且他多产——在 1960 年代和 70 年代,他有一段时间在一年内为 20 多部电影谱曲,每月两部,从未打电话或影响作品的质量下降。 我不认为今天活着的电影作曲家没有受到埃尼奥·莫里康内的影响。事实上,他基本上为意大利面条西部片发明了一整套音乐流派,这已经足够了,但他也如此精通所有其他可以想象的音乐流派,这几乎是前所未有的。他为惊悚片和恐怖电影配乐,使他有机会突破电影音乐的界限,并提供了现在被归类为采样、电子声音设计和听觉操纵的早期例子。然后是他的浪漫主题; 他对爱和激情的渴望、狂喜、有时唤起苦乐参半,随着管弦乐的优雅而膨胀,往往令人痛苦、令人心碎的美丽。 我不喜欢莫里康内写过的所有作品,他的电影作品中还有一些尘土飞扬的角落,我还没有探索过,但那些我确实喜欢的配乐,我全心全意地爱着。好,坏,丑。雇佣兵。西部往事。红帐篷。决斗者。卡里夫女人。革命往事。 这种爱。阿隆桑芬。天堂的日子。马可波罗。美国往事。冒险家。教会。义胆雄心。天堂电影院。诺斯特罗莫。云的守护者。海上钢琴师。被拒绝的乐谱美梦成真。爱欲旋律。玛莲娜。命运无常。我可能忘记了一些,这就是他巨大而多样的产出。 我不认为埃尼奥·莫里康内(Ennio Morricone)遗产的全部影响在相当长的一段时间内会得到充分的赞赏,但我确实知道,在我写这篇文章的时候,我可以绝对自信地说,他将成为二十世纪最伟大的作曲家之一——不仅是电影作曲家,而且是作曲家。 |

||||||||||||||||||

2020.7.6 |

||||||||||||||||||

以下是原文

| ||||||||||||||||||

ENNIO MORRICONE REVIEWS, Part 12-120 |

||||||||||||||||||

Ennio Morricone, 1928-2020July 6, 2020

Composer Ennio Morricone died on July 6, 2020, in hospital in Rome, Italy, after suffering complications following a fall at his home, in which he broke his leg. He was 91. Ennio Morricone was born in Rome, Italy, in November 1928. He studied at the Conservatory of the National Academy of Santa Cecilia, where he specialized in trumpet performance and composition. During the 1950s Morricone orchestrated and arranged pop songs for the RCA record label, including some for artists such as Paul Anka, Chet Baker and Mina. While working for RCA Morricone also wrote theater music and classical pieces, eventually going on to form Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanzsa, an avant-garde musical improvisation group considered to be one of the first experimental composers collectives. Morricone began ghostwriting for composers such as Armando Trovajoli and Mario Nascimbene in the late 1950s, before making his credited film debut in 1961 for director Luciano Salce’s Il Federale (The Fascist). He worked almost exclusively in Italian cinema in the 1960s, but started to gain some international prominence for his work with director Sergio Leone, a former classmate, whose ‘spaghetti westerns’ starring a young American actor named Clint Eastwood became unexpected hits. A Fistful of Dollars (1964), For a Few Dollars More (1965), The Good the Bad and the Ugly (1966) and Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), as well as the Burt Reynolds vehicle Navajo Joe (1966), introduced the world to his idiosyncratic personal style, mixing a traditional orchestra with unusual percussion effects, gruff chanting voices, unusual whistles courtesy of Alessandro Alessandroni, and the soaring beauty of the voice of his friend, soprano Edda dell’Orso. These scores became hugely influential and massively popular, quickly cementing his reputation as one of Europe’s leading film composers. The late 1960s and early 1970s saw Morricone broaden his horizons, scoring films across Europe in every genre imaginable, and making his first forays into Hollywood. His frequent collaborators included directors such as Dario Argento, Marco Bellocchio, Bernardo Bertolucci, Mauro Bolognini, Terrence Malick, Giuliano Montaldo, Alberto Negrin, Pierpaolo Pasolini and Gillo Pontecorvo, and he scored such popular and acclaimed films as Two Mules for Sister Sara (1970), Duck You Sucker (1971), My Name is Nobody (1973), Salò (1975), Novecento (1976) and Days of Heaven (1978), for which he received his first Academy Award nomination. The 1980s and 1990s saw Morricone being employed much more frequently by American directors, and some of his most popular scores of the period were for box office successes such as John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982), Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables (1987), Bugsy (1991), In the Line of Fire (1993), Barry Levinson’s Wolf (1994) and Disclosure (1994), as well as critical masterpieces such as Once Upon a Time in America (1984), Roland Joffé’s The Mission (1986), Casualties of War (1990), and Giuseppe Tornatore’s trio Cinema Paradiso (1991), The Star Maker (1997) and The Legend of 1900 (1999). After having his score for What Dreams May Come rejected in 1998 (where he was replaced by Michael Kamen), and suffering a quite torturous post-production period on Brian De Palma’s Mission to Mars in 2000, Morricone removed himself from the Hollywood composing scene, preferring instead to stay mostly in Europe, writing for mainly Italian film and television projects, where he remained prolific, scoring more than 75 films after the turn of the millennium. His final American film, The Hateful Eight for director Quentin Tarantino, earned him a long-overdue Academy Award for Best Original Score in 2015; Morricone had been nominated for five Academy Awards – for Days of Heaven, The Mission, The Untouchables, Bugsy, and Malèna in 2000 – without winning, before being awarded an Honorary Oscar in 2007 “for his magnificent and multifaceted contributions to the art of film music”, becoming only the second composer after Alex North to be so honored. In addition to this, Morricone won three Golden Globes (from 9 nominations), six BAFTA Awards, four Grammys, and ten David Di Donatello Awards in his native Italy. The main title from The Good the Bad and the Ugly, as well as that score’s conclusive piece “Ecstasy of Gold”, became two of Morricone’s signature pieces. Morricone’s non-film composition “Chi Mai”, which featured in the films Maddalena (1971) and Le Professionnel (1981), as well as the TV series An Englishman’s Castle (1978) and The Life and Times of David Lloyd George (1981), was also immensely popular, and because of its appearances on British TV, the theme reached number 2 on the UK Singles Chart in 1981. In addition to his film work, Morricone wrote numerous classical works and conducted many orchestras worldwide, including the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic and the London Symphony Orchestra. He was one of the main conductors of the Orchestra Roma Sinfonietta since the mid-1990s, and conducted over 200 concerts worldwide since 2001. He lived in Rome with his wife, Maria Travia, whom he married in 1956. They had three sons and daughter: Marco, Alessandra, Andrea – who is also a composer and conductor – and Giovanni, a filmmaker who lives in New York City. ========================= At this point I would like to offer a couple of personal reflections on Morricone. I was fortunate enough to see him in concert in London twice, at the Barbican in 2001 and then at the Royal Albert Hall in 2003, and both events were spectacular celebrations of the man and his music. I only met him face-to-face once, in February 2016, when he travelled to Los Angeles to attend the Academy Awards. The Society of Composers and Lyricists arranged a reception for that year’s music nominees, and I was able to shake his hand and pose for a quick photograph with him. As he famously refused to learn English, and considering that my Italian is virtually zero, I said just two words to him – ‘mille grazie’ – to thank him not only for the photo, but as a completely inadequate ‘thank you for everything you have done for music in your life’. He replied with a ‘prego,’ and gave me a tiny hint of a smile of acknowledgement, and that was that. But one magical thing I did witness was a conversation between Morricone and John Williams, who was also nominated that year. These two giants of music were sat, heads together, engrossed with each other for more than 15 minutes, animatedly chatting away while Ennio’s son Giovanni translated. I was standing just a few feet away from them, and I couldn’t really tell what was being said, but it struck me that this was something of an iconic moment. It was like watching a conversation between Mozart and Beethoven, Shakespeare and Dickens, Da Vinci and Van Gogh, had these people not been separated by time and geography. It’s almost impossible to overstate just how influential, just how brilliant, just how much of a genius Morricone was. Morricone didn’t compose at a piano, nor did he use a computer. He used a pencil and a piece of staff paper, and just wrote whatever was in his head. It’s astonishing to think that, one morning, he sat down to write some music, and then by the end of the day “The Ecstasy of Gold” existed in the world. Or “Gabriel’s Oboe”. Or “Deborah’s Theme”. Or any of the dozens and dozens of iconic themes that he penned over the course of his career. And he was prolific – there were years in the 1960s and 70s where he was writing more than 20 scores in a single year, two per month, without ever phoning it in or allowing for a dip in quality. I don’t think there is a film composer alive today who has not been influenced in some way by Ennio Morricone. The fact that he essentially invented an entire genre of music for spaghetti westerns is achievement enough, but the fact that he was also so proficient across every other conceivable genre of music is almost unprecedented. His scores for the giallo thrillers and horror movies gave him the opportunities to push the boundaries of what film music could be, and offered early examples of what would now be classified as sampling, electronic sound design, and aural manipulation. And then there are his romantic themes; his longing, rapturous, sometimes bittersweet evocations of love and passion, which swell with orchestral elegance and are often achingly, heartbreakingly beautiful. I don’t love everything Morricone has ever written, and there are still dusty corners of his filmography that I have yet to explore, but those scores I do love I love wholeheartedly. The Good the Bad and the Ugly. Il Mercenario. Once Upon a Time in the West. La Tenda Rossa. Vamos A Matar Compañeros. La Califfa. Giù La Testa. Questa Specie d’Amore. Allonsanfàn. Days of Heaven. Marco Polo. Once Upon a Time in America. La Venexiana. The Mission. The Untouchables. Cinema Paradiso. Nostromo. I Guardiani del Cielo. The Legend of 1900. The rejected score for What Dreams May Come. Canone Inverso. Malèna. Fateless. And I’m probably forgetting some, such was his immense and varied output. I don’t think the full impact of Ennio Morricone’s legacy will be fully appreciated for quite some time, but I do know that, as I write this, I can say with absolute confidence that he will go down as one of the greatest composers – not just film composers, but composers, period – of the twentieth century. Addio, Maestro. |

||||||||||||||||||

July 6, 2020 |

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

Jon 是一位电影音乐评论家和记者,自 1997 年以来一直担任全球最受欢迎的英语电影音乐网站之一 Movie Music UK 的编辑和首席评论员,并且是国际电影音乐评论家协会 (IFMCA) 的主席。在过去的 20多 年中,Jon 撰写了 3,000 多篇评论和文章,并进行了多次作曲家采访。在杂志刊物方面,乔恩曾为《电影配乐月刊》、《原声带杂志》和《电影音乐》等出版物撰写评论和文章,并为普罗米修斯唱片公司的两张经典 Basil Poledouris 配乐专辑《Amanda》和《Flyers / Fire on the Mountain》撰写了衬垫注释。他还为汤姆·胡佛 (Tom Hoover) 于 2011 年出版的《Soundtrack Nation: Interviews with Today's Top Professionals in Film, Videogame, and Television Scorering》一书撰写了一章。在1990年代后期,乔恩是伦敦皇家爱乐乐团的电影音乐顾问,并与他们合作拍摄了约翰·德布尼(John Debney)的音乐电影《相对价值》(Relative Values)和奥利弗·海斯(Oliver Heise)的音乐《佛陀的指环》(The Ring of the Buddha),以及与兰迪·纽曼(Randy Newman)合作的一系列音乐会。2012年,乔恩在波兰克拉科夫举行的第五届年度电影音乐节上担任“电影节学院”主席。他是作曲家和作词家协会的成员,该协会是作曲家、作词家和词曲作者从事电影、电视和多媒体工作的首要非营利组织。 |

||||||||||||||||||

2023.12.20 |

||||||||||||||||||

2023 手机版 |

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||